Origin: a leaf on the world map

1. Legends and early traces

The origins of tea are often woven into myths. In China, the legend of Shennong recounts that he accidentally discovered tea leaves when they fell into a pot of boiling water, imparting a pleasant aroma and a refreshing taste. In India, stories associate tea with meditating monks seeking a drink that would help them stay awake. These myths are not strictly historical, but they reflect how early humans associated tea with life, health, and spirituality.

Along with the legends are early written records. Documents from the Han Dynasty mention the use of tea leaves as medicine, and by the Tang Dynasty, tea had become an indispensable part of cultural life. These texts confirm that very early on, tea had stepped out of the realm of plants and become an element of civilization.

2. Two lines of trees, two cultural branches

The tea plant belongs to the species Camellia sinensis , but evolution and geographical distribution have resulted in two major groups: the small-leaf Chinese ( sinensis ) and the large-leaf Indian ( assamica ). The small-leaf variety is associated with East Asian culture, where the art of preparing and enjoying tea has been refined over centuries. The large-leaf variety, which is suited to tropical climates, thrives in South Asia, where tea is prepared strong, often with milk and spices.

Two distinct lines of tea plants lead to the formation of two streams of tea culture: one side tends towards subtlety, gentleness, exploiting elegant layers of flavor; the other side tends towards strength, richness, suitable for working life and energy needs.

3. From medicinal herbs to spiritual drinks

Initially, tea was used as medicine: to cool down, reduce fatigue, and purify the body. But gradually, people learned how to process it to turn the bitter taste into a pleasant, delicious one. From then on, tea went beyond the medical category to become a spiritual drink. It appeared in Zen monasteries, accompanying sutra reading and meditation sessions; it entered poetry, becoming a spiritual instrument for literati and artists. Tea is no longer just a medicinal plant, but has become a cultural symbol.

4. The way of spreading

From southwestern China, tea spread in many directions. Overland, tea traveled with caravans along the Silk Road to the Western Regions and beyond. By sea, from ports in eastern and southern China, dried tea leaves crossed the ocean to Japan, Southeast Asia, the Middle East, and Europe. This process not only moved the product, but also the knowledge of tea processing and drinking habits.

When it reached Japan, tea became a central part of Zen Buddhism, developing into the Tea Ceremony. When it reached the Middle East, tea was combined with sugar and mint, creating its own identity. When it reached Europe, it became an aristocratic drink, leading to huge import demands and political upheavals.

5. From localization to globalization

Tea was localized wherever it went, changing its preparation and drinking methods to suit local customs. But at the same time, large-scale trade made tea a global commodity. Standardization of production, packaging, and transportation created hubs of tea trade, making it one of the world’s most influential agricultural products.

6. Cooking techniques and flavor language

A key point in the development of tea is the processing technique. From withering, fixing, rolling, drying, brewing — each step creates a chemical change, leading to an infinite variety of flavors: floral, honeyed, nutty, fruity, smoky, woody, milky. It is here that tea becomes a sensory language, where each culture speaks with its own unique flavor accent.

7. Conclusion

The origin of tea is a story of intersections: between nature and civilization, between medicine and aesthetics, between localization and globalization. The humble tea leaf has traveled a long journey to become a cultural symbol and strategic commodity. Understanding this origin is the first step to delving into the next journey: the role of tea in spiritual traditions, art, and social life throughout the ages.

Tea and Religion: From Zen to Folk

Introduction — a bridge between matter and spirit

Tea is more than just a beverage; in many cultures, it is a spiritual medium . When a cup of tea is offered, it is both a physical act (water + leaves + fire) and a symbolic act, a gesture that connects people to each other and to a larger realm—zen, ancestors, or a community of faith. This chapter explores that depth: examining tea as a tool of religious practice, as a symbol, and as a ritual space where each gesture is transformed by meaning.

1. Tea and Meditation: Tools of Mindfulness

Tea in the life of a Zen master

In the Zen/Chan tradition, tea plays a practical role—helping practitioners maintain mindfulness during extended meditation sessions—but that role is more than just utilitarian. Tea is understood as a stimulant for attention , a medium that helps the mind focus without being tied down. Drinking tea in Zen is both an act and a practice: breathing, noticing the bitter taste, feeling the warmth—all are exercises in presence.

From Zen to Tea Ceremony: Zenizing Aesthetics

In Japan, the tea ceremony (chanoyu) exemplifies how a religious practice can mobilize aesthetics to teach: Zen philosophy permeates space, objects, and movements. Four central concepts— wa (harmony), kei (respect), sei (cleanliness), and jaku (silence)—transform a bowl of tea into a teaching tool. Each gesture—scooping water, stirring, pouring tea—is reduced to a lesson in living: harmony, respect, purification, and serenity.

2. Taoism, Confucianism and the Evolution of Tea as a Moral Symbol

Tea in the Taoist Ideological Framework

With its spirit of being close to nature, Taoism sees tea as a way to “become one” with nature: tea soothes the body, regulates the qi, and is in line with the ideal of longevity and the spirit of “natural Taoism”. In some traditions of internal medicine, tea has been considered a drink that supports the practice of health preservation.

Tea in Confucian discourse

Confucianism emphasized propriety and social order—tea, in this context, was a symbol of elegance and scholarship. Among the literati, drinking tea was not just for taste, but a cultural act: making tea and offering tea were small rituals that demonstrated etiquette, respect, and self-forbearance. Tea became part of the scholarly “temperament”: when drinking tea, people simultaneously practiced a disciplined way of life.

3. Tea in folk beliefs: ceremonies, offerings and communication with ancestors

Tea as a gift

In many East Asian cultures, tea is a common offering in family rituals: offering to ancestors, inviting gods, or in marriage ceremonies—offering tea is an act of giving even without speaking. Here, tea is “wordless language”: a cup of tea encapsulates sincerity, respect, and social contract.

Tea in the rites of birth and death

Tea appears in birth, wedding and funeral rites, with different meanings but the same function: connection, transition, comfort. For example, at funerals, tea can be used to welcome visitors, to show respect, and to help the mourners stay awake during the long rituals.

4. Tea and other religions: regional variations

Tibet and butter tea

In Tibet, butter tea is a daily beverage but also closely linked to the local Buddhist religious life: butter tea nourishes the body in the harsh climate and is also an item of worship, travel, and hospitality.

South Asia: Tea in Religious and Community Life

In India, while tea (chai) is not a core religious ritual item like coconuts or flowers, drinking and serving tea is part of community life: from temple benches to roadside stalls, tea connects people. At many ceremonies, tea is part of social reception—a gesture of hospitality.

5. Religious spaces — from meditation halls to communal houses, from assembly halls to bamboo beds

Tea changes its meaning depending on where it is offered: in a meditation room, a cup of tea is a means of spiritual practice; in a village temple, a teapot is a tool for communal reconciliation; in a family, a cup of tea offered to guests is a humane gesture. The space transforms a material act into a sacred act: the utensils, the arrangement, and the accompanying language create the sacred ritual.

6. Objects, rituals and meaning transformation

Tea utensils—bowls, teapots, spoons, tea tables—are more than just tools; in many traditions they are symbolic, cared for as sacred objects. For example, the missing ceramic in a Japanese teapot may be appreciated for its “imperfections” (wabi-sabi)—the very “imperfections” that provide a philosophical lesson: accepting impermanence.

7. Gender, power, and social roles in religious tea practices

Tea practices are not gender-neutral: in many societies, women are responsible for preparing tea in the home and in ceremonies, while public tea spaces (such as the scholar’s table, teahouse) are often dominated by men. These divisions reflect social structures: tea is both a tool of ritual and a means of expressing soft power (hospitality, patronage).

8. The process of transformation: commerce, urbanization and religious revival

As tea became commercialized and spread to the cities, the sacred spaces of tea (zen temples, village temples) were displaced to tea shops, tea rooms, and cultural theaters. However, in the last century, we have witnessed a “resurrection”—tea reinterpreted by the mindfulness movement, traditional preservation groups—where the religious tea is reinterpreted for modern spiritual needs.

Conclusion — Tea as a Religious Dialect

Tea functions as a religious “dialect”: its use, its form of offering, its accompanying objects, and its communal context all form a system of symbols. To understand tea in religion is to see how people organize their spiritual lives: through small actions, through bitterness and warmth, through ritual repetition. In every culture, tea allows people to speak of the sacred—both intimately and deeply.

Tea drinking rituals and culture by region

The tea ceremony is a secret language: it speaks not only in flavor but also in the distance between hands, the swing of a spoon, the shape of a bowl. In each land, the way people pour, stir, sip, and pass the cup tells a story about their history, climate, social structure, and hidden values. Here are the ritual forms—not to classify them rigidly, but to listen to each voice in the global cultural chorus.

China — Gongfu: the art of diligence

In China, the tea ceremony is often exploratory: the brewer is like a musician, each pour revealing a note of aroma. Gongfu is not simply a technique, but a way of reading the history of a batch of tea—from the soil, the variety, to the way the leaves have been processed. Yixing teapots, small cups, wooden trays—all constitute a small stage; time, temperature, and amount of leaf are balanced by experience. Gongfu spaces can be warm living rooms, quiet teahouses, or bustling porches; in all contexts, the ritual demands attention, giving the drinker the opportunity to hear the “sound” of the leaves. Socially, Gongfu is a manifestation of culture: enjoying details is a way of expressing knowledge, aesthetics, and character.

Japan — Chanoyu: Tea as a Lesson in Life

Tea in Japan is Zenized. Chanoyu—the way of tea—condenses the entire philosophy of Zen into a series of movements: sweeping, washing, scooping, stirring, handing. The concepts of wa, kei, sei, jaku (harmony, respect, cleanliness, tranquility) are not mere slogans; they are laws of hand movement. A bowl of matcha placed on a tatami mat can be read as a lesson in humility, accepting impermanence, and finding beauty in imperfection (wabi-sabi). On a personal level, chanoyu is a tool for cultivating the mind—on a social level, it is a ritual structure, defining the relationship between inviter and invitee, between artisan and guest. Tea here is tactile walking meditation.

South Asia — Chai: the drink of public life

Tea in India and much of South Asia is a noisy, warm practice: the pot boils, steam rises, paper cups or cheap copper ones are passed around on the sidewalk. Chai masala—tea mixed with milk and spices—is the drink that sustains working bodies and nourishes social life. At crossroads, small tea shops are courts, parliaments, and debate stages. Here, ritual does not seek subtlety; it seeks continuity, sharing, efficiency. Tea is a social contact: offering tea is an invitation to join a conversation, a moment of respite from the chaos.

Tibet and the Himalayan Plateau — Butter Tea: Survival in the Cold

In the highlands, tea became a means of survival. Butter tea—strongly boiled tea mixed with yak butter and salt—provided energy and warmth in the harsh climate. The ritual of drinking tea in these regions was closely tied to religious life and hospitality: a bowl of butter tea passed to a guest was a sign of warmth and friendship. When monks gathered, when pilgrims stopped, tea not only warmed the body but also established a communal bond; it was an act of kindness between man and harsh nature.

Middle East & North Africa — Tea as a Performance of Hospitality

From the Turkish teapot to the Moroccan mint jug, tea is a social greeting in these regions. It is poured high to create a foam, served in small cups, and the pouring ritual becomes a display of generosity. A cup of tea here declares: welcome, respect, and conversation. A sense of honor and hospitality is conveyed through each gesture—pouring, offering, lifting—as a subtle language of status and affection.

Europe — Tea as a Social and Aesthetic Phenomenon

As tea entered Europe, it was transformed by leisure, status, and taste: from medicine to social ritual. In England, the afternoon cup of tea was a symbol of schedule and status; the tearoom was a place of exchange, where literature and politics sometimes flourished. Large pots, porcelain, tablecloths—European etiquette emphasized presentation and consistency of flavor, to avoid surprises and maintain politeness. Tea in Europe was a social order, where every detail on the table could be read as a sign of taste and class.

Vietnam — tea as the rhythm of community life

In Vietnam, tea is seen in everyday life with a rustic and sentimental touch: teapots, clay pots, and small cups are placed on bamboo tables, sitting on cots at the entrance of the alley. Offering tea is a small but meaningful ritual — it connects people, shows hospitality and respect for ancestors. Lotus-scented tea and jasmine tea are proof that even in a common environment, the need for sophistication still exists. Here, the tea ceremony is both simple and multi-faceted: sometimes it is quiet with a hot cup, sometimes it is bustling in the market, and always the thread that keeps the community in rhythm.

Comparison — why are the rituals different?

In general, ritual forms are shaped by four basic factors: climate (coldness, heat needs), economy (industrialization or subsistence), social structure (hierarchy, public or private), and materials (plant variety, processing method). In cold regions, tea is strong and nutritious; in scholarly societies, tea is refined into art; in the marketplace, tea is a tool for instant connection. Ritual is a product of living conditions and a means of reproducing identity.

Conclusion — a cup of tea as an anthropological map

Every tea ceremony is an anthropological snapshot: through it we read the climate, read the power relations, read how a community cares for itself and communicates. As part of a cultural journey, the tea ceremony is more than just a taste experience; it is a record of gestures and habits, a collective memory that continues to be written as people move, urbanize, and reclaim quiet spaces. The humble cup of tea thus bears a great responsibility: it holds the story of how we live, think, and share.

Tea and trade: corridors of civilization and the movement of leaves

There are small objects that, when passed around, carry a language of power. The tea leaf is one of them. As it leaves the branch, enters the cloth bag, and then boards the train, its every movement is simultaneously a note in the commercial, political, and cultural symphony of humankind.

1. The first corridors — from camel back to ship hold

Tea begins its journey not with a formal map but with a network of relationships: the picker trusts the merchant, the merchant trusts the carrier. On ancient routes—the Silk Road—tea is packed in compressed cakes, placed alongside salt, animal skins, and herbs. On the cold steppes, a stick of tea can be exchanged for a horse’s life; in a desert market, a cup of tea is a greeting.

As the seas opened up and Far Eastern merchant ships began to cross the Indian Ocean, tea left continental borders and entered another universe: ship holds, ports, and trading floors. Tea traveled with porcelain, silk, and spices—and in each port of call, drinking habits, preparation methods, and enjoyment practices were traded like an invisible commodity.

2. The trading companies — when capital and merchant ships combined power

The emergence of large European trading companies—with their capital, fleets, and government protection—changed the nature of the game. Organizations like the East India Company (and its Dutch counterparts) didn’t just buy the product; they organized, promoted, and directed where it was grown, who picked it, and how it was packaged. With exclusive royal authority, they transformed tea from a local commodity into a strategic asset on the political map.

This corporate power boils down to this: they can orchestrate the flow of tea—deciding who gets access to good sources, who pays the price, who benefits. And when economic interests meet political interests, tea quickly becomes a symbol of power: whoever controls tea, somehow owns the global economic veins.

3. Colonization of production — seeking to break monopolies

As European demand for tea skyrocketed, a paradox emerged: traditional suppliers (mainly from China) controlled the technology and varieties. The solution for the great powers was to take tea plants from their native lands and plant them in colonial gardens. In India and Ceylon (Sri Lanka), people set about turning hillsides into tea gardens. Breeding, testing, and farming were carried out under the collective model to meet the demands of the Western market—a deliberate attempt to break the monopoly and create their own supply.

The act of turning other lands into tea gardens clearly shows that trade is not just about exchanging products, but also about transferring technology, planning territories and restructuring livelihoods. Tea is no longer just a product of one region, but has become the product of a transcontinental economic system.

4. Historical events: from the Boston Tea Party to the Opium Wars — when tea cups became political symbols

Tea, because of its economic value and its symbolism of power, has often found itself at the center of major conflicts. A prominent example in the West is the Boston Tea Party (December 16, 1773): when a tea ship owned by the British East India Company was thrown overboard by American colonists protesting what they considered unfair privileges and monopolies. The action, though tax-related, turned a shipment of herbs into a political cause—and one of the sparks that led to revolution.

In the East, trade relations around tea also generated conflict in other ways. As European demand for tea created a net flow of silver into the East, merchants sought to balance the trade. One painful consequence was the British-led opium trade into China to make up for the trade deficit; when the Chinese government tried to contain it, the confrontation escalated into the Opium Wars (a series of conflicts between China and Western powers in the 19th century). Postwar treaties opened ports, ceded territory, and weakened traditional governance, changing the structure of tea trade and the autonomy of producing regions.

The two events above illustrate a painful reality: tea not only stimulates the taste buds, but also promotes power clashes, when economic interests go hand in hand with national policy.

5. Cultural consequences — changing drinking habits and symbolic meanings

International trade and colonial politics not only changed where tea was grown, but also how it was consumed. As tea reached Europe, it was adapted to tastes and living conditions: processing methods and tea selection gradually evolved to accommodate new travel distances and new dietary habits. Among the European aristocracy and burghers, tea became a social symbol—the afternoon tea ceremony, the porcelain tea set, and the way tea was served indicated status and style.

Conversely, within the native tea regions themselves, the shifting trade landscape has also affected perceptions of tea: sometimes tea is directed more toward export than domestic consumption, and traditional processing knowledge is adapted to serve foreign tastes. Tea is thus more than just a beverage; it becomes a mirror of the interaction between culture and money, between taste and policy.

6. It turns out: the leaf is like historical text

When reading the history of the tea trade, one should not simply look at the number of ships or the orders; one should read the leaf as a text. In each shipment there is the memory of the land, the decision of the administrator, the reaction of the picker, and the habit of the drinker. Economic decisions—where to grow, who to pick, how to package—are imprinted on the culture of consumption. And when power intervenes—through taxes, treaties, force—the leaf is drawn into the political vortex.

Tea in Vietnamese culture: from family customs to public culture

A cup of tea in Vietnam is more than just steaming on the table; it is a gesture that has been repeated enough times to become a language. In families, in village communal houses, on the streets, the custom of offering tea, the way of pouring it, the type of tea chosen—all have social, religious, and aesthetic meanings. This chapter does not recount the history of cultivation or processing techniques; it reads tea as behavior: how Vietnamese people use tea to communicate, to perform rituals, to maintain politeness, and to express taste.

1. Tea in the family — a daily ritual and symbol of hospitality

At the smallest scale — the living room, the porch, or the kitchen table — the act of offering tea serves as the initial ritual for any interaction. When guests enter, a pot of boiling water, a few small cups, and a stick of tea are enough to immediately change the state: communication officially begins, the atmosphere of the visit is softened, and the words become more formal.

The arrangement and order of pouring cups reflects hierarchy: cups for elders or honored guests are usually brought first; the head of the family makes a suggestion, and the guest responds with thanks. This behavior fosters a small set of rituals—without words—that help family members and guests read each other, balancing the relationship through purely physical gestures: pouring—giving—raising—sipping.

2. Tea in family ceremonies — offerings, death anniversaries, weddings

In solemn ceremonies, tea holds an irreplaceable position. On the ancestral altar, a cup of tea is offered as a symbol of sincerity; the steam rising from the cup is a call to the deceased, both sacrificial and telling. In traditional weddings, the ritual of offering tea becomes part of the ceremony: the son-in-law and daughter-in-law offer tea to their parents, exchanging tea for a part of their filial piety and accepting new responsibilities; that action turns wishes into deeds, making blood relations affirmed by action.

At death anniversaries, a cup of tea is not simply a beverage but a connection between the past and the present: the living make it, the living invite it, and through that invitation, the community re-establishes a common memory.

3. Tea as a gift — exchange, respect, and status symbol

Tea is a popular gift with many layers of meaning. A beautiful box of tea given on Tet, as a visit or as a thank you is not just a material to drink; it is an expression of thoughtfulness, of a relationship that wants to be maintained. In the culture of giving tea in East Asia, giving tea is a social act: the giver shows his aesthetic taste, the receiver responds with attitude and wishes.

On a more subtle level, the choice of tea (lotus-scented tea or premium highland tea) is a way to communicate taste, origin and level of respect — that is, knowledge about tea becomes a form of cultural capital.

4. Street Tea and Public Culture — From Iced Tea to Sophisticated Teahouses

Alongside family rituals, there is a rich public tea culture. On a street corner, a glass of iced tea or a small pot placed among a group of friends is a symbol of everyday life: cheap, quick, and intimate. Sidewalk tea shops have unwritten conventions — places where people gather to discuss village affairs, politics, or just to take a few minutes off from the hustle and bustle.

In today’s urban areas, there are also spaces for tea drinking with a different consciousness: tea shops specializing in serving loose leaf tea, tea tasting sessions, or spaces for “tea drinking” in a sophisticated way. This phenomenon is an indication that tea drinking culture is polyphonic — there is still “tea for everyday life” and at the same time “tea for enjoyment” with a completely different way of behaving.

5. Tea varieties and their cultural and social locations

Not all teas are suitable for all occasions. Loose leaf green tea, scented tea (lotus, jasmine) or handcrafted oolong tea — each corresponds to a style of communication. Loose leaf green tea is often associated with simple, convenient invitations. Scented lotus tea and jasmine tea appear when it is necessary to show sophistication; the scent is considered a sign of thoughtfulness and aesthetics. Oolong tea, with its “enjoyable cup” character, is easily used when the drinker wants to focus on the senses, on a deeper exchange.

Tea choice is therefore an act of communication: the host tells the guest through taste how they perceive the meeting—respectful, intimate, or formal.

6. Tea, Generations and Cultural Shifts

The way tea is consumed in Vietnam is not fixed; it changes with the times. The older generation maintains the habit of “clay pots, small cups”, while the younger generation expands the consumption spectrum: tea bags, cold brew, mixed tea in harmony with the trend of fast consumption. At the same time, there is a counter-movement: young people turn to tea as a restorative behavior – relearning how to enjoy tea, appreciating its origin and technique – as a reaction to the urban pace.

This is a dialectic: tea is both a conservation element and a creative material; it is subjected to the pressure of modernization but also reinterpreted in new contexts.

Conclusion — Tea as a Social Connection

Tea in Vietnam is a link between individual and community, between the living and ancestors, between guest and host. It registers social order through the act of pouring; it speaks through scent when trivial words become superfluous. The humble cup of tea is a complete practice: it comforts, affirms, and signifies. To read Vietnamese tea culture is to read how Vietnamese people organize relationships—subtle, repetitive, and full of hidden meanings.

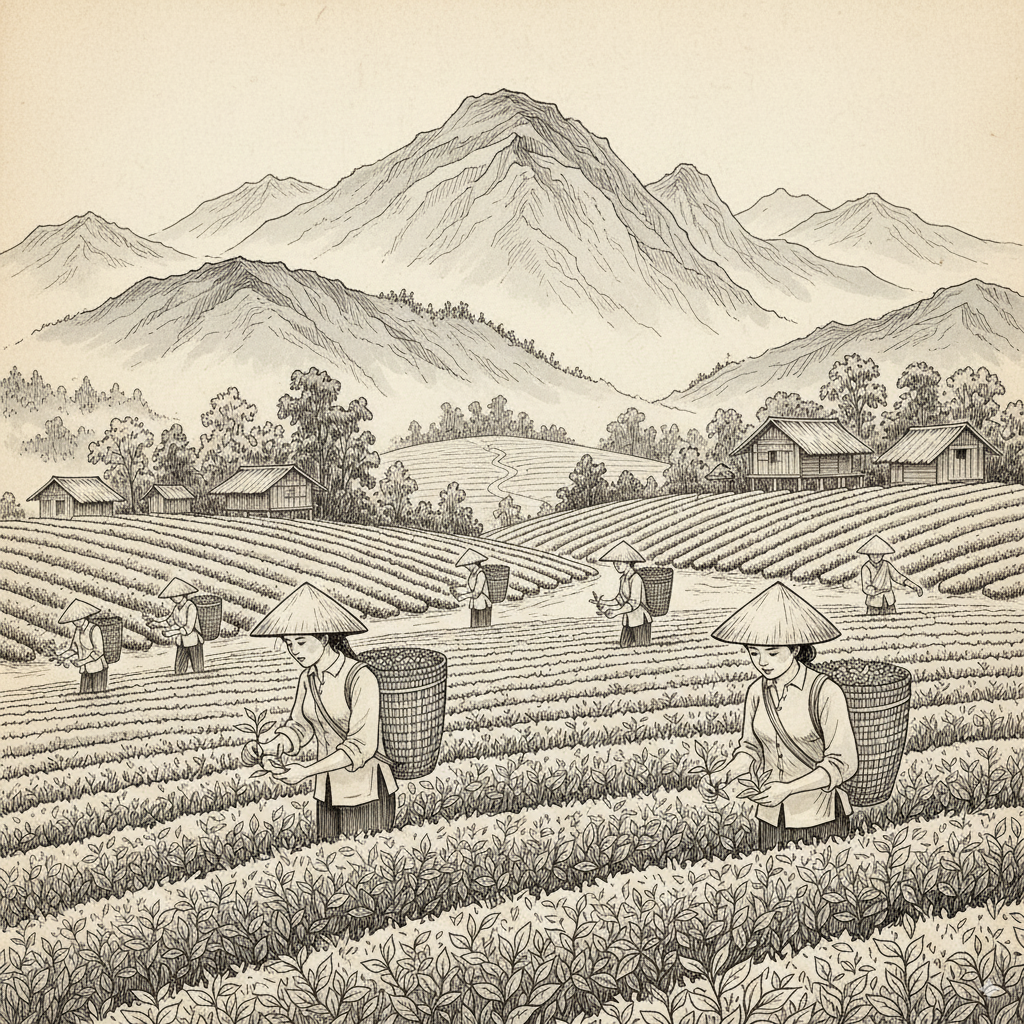

Farming journey: model in Vietnam

Introduction — soil, seed and skill: the triangle that shapes a teacup

Tea cultivation is more than just the growing of the plant; it is a series of cultural decisions. When people choose the variety, choose where to plant the beds, decide whether to pick by hand or by machine—they are writing a language about how tea will be drunk, who will be served tea, and under what circumstances. This chapter traces the transformation of Vietnamese cultivation—from small home gardens to plantations, from French experimentation to the birth of Oolong in the highlands—but always returns to a central question: how these changes have written into Vietnamese tea culture.

1. From homestead to plantation: shifting cultural models and meanings

Traditionally, tea was a family business: small gardens, hand-picking, secrets passed down through generations. Tea plantations were often tied to the home, to the hands of mothers and fathers, to conversations after picking. The tea served internal needs—to entertain guests, worship, and entertain friends.

Under the colonial era, the scenario changed: plantations were planned, areas expanded, and cultivation techniques became more systematic. This created two parallel streams in tea culture: one that remained artisanal, meticulous, and local; the other concerned with mass production, serving a large market. Tea culture thus also stratified: tea for everyday life and tea for commerce—each carrying a different social message.

2. Historical milestones: French period and 1927 mark

The 1920s marked decisive experiments. Geological surveys and seed trials conducted by the colonials had led to the emergence of new tea regions in the highlands. In 1927, with research at Cau Dat and along Highway 20, Bao Loc gradually emerged as a potential tea region. Experimental methods (even trials of seeding by airplane to find suitable areas) showed a new way of thinking: tea trees were seen as a source of raw materials that could be moved, multiplied, and brought into the commercial network.

Tea culture thus expanded: the highlands produced new types of tea that were previously rare in the lowlands—bright teas with a light aroma, or teas with a strong flavor depending on the region. Local people, workers, and residents gradually developed new tea-drinking rituals compatible with the region’s products.

3. Bao Loc — from soil to enjoyment habits

Bao Loc, with its early morning mist and high altitude, has not only become a successful place for growing tea but also nurtured a unique aesthetic for tea drinking. As tea gardens expanded along Highway 20, the surrounding life broke out into cultural patterns: picking in the morning, drinking in the afternoon; pedestrians were offered tea; roadside stalls appeared to serve passersby. Bao Loc tea entered the lives of the locals not simply as an export product — it was the rhythm of life, the smell of mist, the way people started a new day.

4. Oolong — a new chapter: varieties, techniques, and enjoyment (1988–1992)

In the late 1980s, another movement began: Oolong varieties were introduced, initially incubated in Dak Nong and then transferred to Bao Loc. From 1989–1992, Oolong in Bao Loc began to be grown and processed on a significant scale. This was not just the import of a new variety; it was the introduction of a series of techniques—shaken, semi-oxidized, elaborately dried—that required skill and time.

Tea culture changed accordingly: Oolong, with its complex aromas and slow-drinking methods, gave rise to more refined tea-drinking practices—cupping, multiple pours, attention to clarity and aftertaste. Drinkers began to realize that there were cups of tea to be “savoured” rather than “sips”. Oolong set new standards for “tea as a gift” and “tea to be enjoyed”.

5. Picking techniques and cultural significance of the picking hand

A key point is always hand-picking: choosing buds with 1 + 2 young leaves or 1 + 3 depending on the product purpose. Hand-picking is not only about quality—it is also a cultural sign: the hand-picking records time, season, and care. The tea garden where hand-picking is still the place to keep the rhythm, where secrets are passed on: when to pick in the early dew, how to move buds to the field to avoid unwanted oxidation, how to classify by eye. From this arises a kind of “professional language”: listening to the workers talk about “the water content of the buds,” “the crispness of the stems”—that is the vocabulary of a tea-making culture.

6. Nursery, seed selection and technology localization

Nursery practices—from Dak Nong to Bao Loc—reflect a cultural practice: not all imported varieties survive intact in their new environments; people have to nurture, select, and sometimes cross-breed to suit the local soil and taste. Nurseries are places where knowledge continues: engineers, artisans, and gardeners read the seasons, observe adaptations, and take notes. The process of selecting varieties is therefore a process that shapes both the flavor and the way tea is later used.

7. Passing on the profession: from family to processing workshop

Although the scale has changed, the craft remains the cultural core. From mother to child, how to smell buds, to artisans teaching workers how to arrange leaves in drying batches, that knowledge is not just a technique but a kind of cultural capital. The first successful batch of Oolong in Bao Loc is the result of a chain of craft transmission: from nursery to workshop, from simple laboratory table to systematic sensory description.

8. Post-memory: farming writes how we drink

Looking back, tea cultivation and tea culture are two sides of the same coin. New varieties were introduced, processing techniques changed, plantations sprang up—all of which shaped how tea was served, how it was given, and how it was perceived as a part of life. The seeds, the soil, and the hands that picked them all imprinted a story into each cup of tea: of the place where it grew, of the gardener, and of the community that drank it.

Conclude

The journey of tea cultivation in Vietnam is a cultural journey: each technical change, each imported variety, or each area chosen for gardening has renewed the way people consume tea — from the simplicity of the porch to the solemn tea ceremony. Reading the history of cultivation is reading the history of the tea cup: there, the land and the craft co-create the drinking moments — and it is these moments that are the living culture we call “Vietnamese tea.”

Bao Loc (B'lao): mist, land, people and tea identity

The mist in Bao Loc is not just a climatic phenomenon; it is a gentle cover for all morning activities, an invisible “fuel” that nurtures the aroma of tea. When the sun has not yet lifted the veil of clouds, the tea hills roll like silver waves — and in that space, a cup of tea is not a utensil, but an interaction between the land, people and the weather. This chapter reads Bao Loc in the language of leaves: from basalt soil, night dew to picking hands, from the history of sowing seeds in the last century to contemporary tea-drinking rituals.

1. Earth and dew — terroir writes the scent

Bao Loc is located on a plateau with mineral-rich basalt soil and a cool climate — a combination of conditions that cause tea plants here to grow at a slower pace than in the lowlands. During the night, thick fog coats the young buds, helping to retain volatile essential oils. The large day-night temperature difference slows the growth of the tea buds, allowing the plants to accumulate more flavor compounds — which is why highland tea buds often have a deep, dimensional aroma and a distinct sweet aftertaste.

In other words, the soil, altitude and dew in Bao Loc do more than just create biological conditions — they write the first “letters” in the region’s taste dictionary: light floral notes, a lingering sweet aftertaste and clear, golden water.

2. History of sowing and product transformation

Bao Loc did not become a “tea region” by accident; it was the result of historical experimentation and artificial selection. Since the French colonial period, there have been surveys to select areas and test varieties — the 1927 mark with the Cau Dat experimental area was the starting point for positioning the plateau as a suitable region. Later, breeding and transfer efforts (including Assam lines and, later, Oolong varieties from Taiwan in the late 1980s and early 1990s) have diversified the agronomic picture of the area.

For tea culture, the consequences were clear: once new varieties and more refined processing techniques were introduced, the way people drank tea changed—from a simple morning cup to a tea ceremony focused on color, clarity, and aftertaste. Oolong, in particular, opened up the need to enjoy tea more slowly—to read the aroma, to listen to the aftertaste—an attitude closer to “hearing” than “drinking.”

3. Hand picking, yard and craft knowledge — culture of the hands

In Bao Loc, hand picking still holds a central place in tea culture. Hand picking — selecting buds of 1 + 2 young leaves, or depending on the product requirements — is not just a technical operation; it is a cultural behavior, where experience is passed down through the years. The picker reads the season like a person: knowing when the buds are covered with dew, when the buds are full of essential oils, when to skip the weak clumps.

The preliminary processing skills at the yard—spreading, withering, and protecting the leaves from shock—are the first steps in the transition between the garden and the processing plant. These actions, when repeated into habit, create a “rhythm” of the craft: the sound of dry leaves, the faint pungent smell, the tea maker’s eyes probing for flavor—all are part of the language of the craft and the culture of tea making.

4. From family customs to local tea ceremonies

Bao Loc tea is present in both daily routines and sophisticated rituals. In the morning in the village, a pot of hot tea is served to workers to start the day; in the afternoon, a cup of tea is served to close guests; and on special occasions – receiving distinguished guests, giving gifts – a box of highland tea is selected for its taste and origin story.

The emergence of Oolong, GABA or specialty teas laid the foundation for new tea-drinking practices: small cupping, multiple pours, attention to the color of the water and the layered aroma. Local tea drinkers began to compare — not only for taste but also for the imprint of the soil: “this tea has a misty scent,” “that tea has a grainy aftertaste” — that is how Bao Loc reads its name through the cup of tea.

5. Landscapes, harvest festivals and collective experiences

The mist-covered tea hills become not only terrain but also a setting for community activities. The autumn harvest season brings with it community activities: from organizing picking days to small gatherings introducing techniques and telling stories about the garden. These events are spaces for knowledge transfer and at the same time a way for the public to experience the culture of tea making: understanding the hands of the pickers, listening to the artisans talk about successful or unsuccessful batches of tea, enjoying a sip of tea right in the middle of the tea bed.

That culture both maintains the locality and opens up to outsiders a direct approach: seeing, touching, tasting — and through that, recognizing the value of the origin.

6. Tea as a gift, as a conversation and as a local memory

Bao Loc tea is often chosen as a gift because it carries the “taste of place” — dew, earth, and hands. The gift of tea is therefore the gift of a piece of local memory; when a cup of tea is poured in a meeting, it immediately opens a story: “this is the tea harvested this morning,” “this is handmade Oolong” — words are replaced by taste, and the story comes alive.

Conclusion – Bao Loc in the mirror of a tea cup

Bao Loc is not a purely geographical name; for tea makers and tea connoisseurs, it is a set of symbols: dew, basalt, young buds, picking hands, drying batches. Bao Loc’s tea drinking culture is the result of a convergence: natural conditions, history of sowing, craft knowledge, and shared community. Each cup of Bao Loc tea is therefore a collection of memories — the taste of the climate, traces of history, and the breath of the person who picked it.

Tea & Experiential Tourism: Turning culture into experience, turning tea into heritage

When talking about tea, people often start with the buds, the hills, and the hands that pick it. But the real experience—what makes tea a proud heritage—occurs when the leaf leaves the garden and meets the hands that know how to read it: the hands of the refiner, the hands of the brewer, and the hands of the tea connoisseur, who together write the story of the cup of tea. There, Tra Tri Viet is more than just a name—it is a workshop, a garden, a repository of memories of the craft; and Quy Tra Coc appears as a local voice, a forum—where the story of tea is revived, examined, and passed on.

1. Try drinking — a cup of tea as a meeting

Trying a cup of Tra Tri Viet tea is not an act of consumption; it is an encounter with hidden rules. The tasting guide invites you to look at the water first, to let your eyes read the color; to inhale, to let your nose act as a map; to sip, to let your tongue record each note: beginning — middle — end. The aroma in Bao Loc often opens with a light floral or fruity note, then briefly changes to butter or nut, and then ends with a lingering sweet aftertaste — the imprint of dew and basalt soil.

In that moment, the drinker is empowered to read: no longer a passive guest, but a co-author of a story. When the Tea Ghost joins in this reading—through articles, podcasts, or videos—it allows the cup of tea to take on additional context: where the garden is, who the artisan is, what the season of dew is like; thus the cup of tea becomes a link between taste and shared memory.

2. Refinery — the “pure” space of the profession

Tra Tri Viet’s refining workshop is where the craft changes its sound: the sound of leaves shaking, the heat seeping in, the scent intensifying as the leaves change shape. But in the experience we want to preserve, the workshop is not turned into a “show” — it is a solemn space where artisans work in front of the audience. Standing next to the workshop, guests can hear the details of the craft: the rhythm of the hands turning the leaves, the timing of dividing the batches, the signs of a “good” or “not good” batch.

The workshop is therefore a classroom. It teaches how to recognize the clarity of water, how to feel the softness of dried leaves, how to distinguish the aftertaste. And most of all, the workshop shows that the creation of a pure cup of tea is a collective journey, where each person—from picking to drying—leaves a cultural trace. When visitors leave the workshop, they take with them not just a packet of tea but a reading frame: the understanding that each taste is the result of a series of actions with a name and a face.

3. Quy Tra Coc – a place for storytelling, experimentation and keeping the soul of the craft

With its rambling narrative and vivid documentation, The Tea Ghost does an important job: placing the cup of tea in its social and cultural context. More than just praising its aroma, The Tea Ghost asks: what does this tea say about the land, the craftsman, the tradition? It opens up dialogues between artisan and drinker, between past and present—making the experience more conscious, giving back to tea the aesthetics that need to be told.

Ghost Tea Valley is also a place where the language of tea is experimented with: from sensory analysis articles to podcast interviews with artisans, where tea is “translated” for a wide audience—from farmers to urban consumers—and so the experience becomes more equitable: one does not need a degree to read a cup of tea; one just needs to be guided and invited to participate.

4. Tea is a proud heritage — experienced as a civic ritual

When the experience is properly guided — tasting carefully, understanding the refinery, listening to the stories told by Quy Tra Coc — tea becomes a living heritage. “Heritage” here is not something old or confined in a museum; it is skill, knowledge, the ethics of inviting guests and sharing; it is the right to be proud when offering a box of Bao Loc tea to the table, because the giver knows that the box contains many layers of memories: soil, dew, craft, and community.

Pride comes not from slogans, but from understanding: when a young city person sips a cup and can briefly describe the “smell of mist” or the “brightness of the water”, the heritage has been passed on in spirit. When an artisan is named and thanked for a good batch of tea, the craft is affirmed. Tea becomes a means for the community to remember itself — a way of saying: this is what we keep and pass on to future generations.

5. Subtle yet not alien — keeping the principle of reviving the experience

The experiences that connect Tra Tri Viet and Quy Tra Coc succeed because they maintain a simple but important principle: honesty with the craft . The craft is not degraded by acting; the information given is not reduced to advertising; the tea cup is still allowed to be silent and speak with taste. Guests are not concerned with time or schedule; they are invited to listen, to taste, to remember.

That is how to turn an economic product into heritage: not by hanging a “heritage” label on a box of tea, but by allowing the tea to tell its story in the voice of the maker and of the land itself.

Conclude

When Tra Tri Viet and Quy Tra Coc truly connect, the most valuable thing is not the number of visitors or the tea samples released — but the spread of knowledge and appreciation. The experience, in the deepest sense, is the moment a person realizes: the cup of tea in front of them is not simply water that has passed through leaves; it is a small book about the land, people, and memories. And it is that book — when opened, read, and passed on — that makes tea a heritage that the people of Bao Loc, Tra Tri Viet, and storytellers like Quy Tra Coc can be proud of.